A Quick Review: The signage outside and inside

THE CLEVELAND MUSUEM OF ART

advertising the Women in Print exhibit, up through June 19,

looms large, and incites curiosity.

The twenty-six recently acquired prints by artists identifying as women using an array of techniques, created over the last several decades, is, in itself, exciting;

did the display live up to the highly esteemed work it presents?

Today, identity moves beyond

“woman.”

Is noting this gendered reference necessary, even appropriate, in the exhibit title?

The Museum’s definition of “women” is not clear in the exhibition didactics, but as it intermingles with the term “female,” one can deduce, thoughtfully, both are deemed very broadly defined.

[Note: Perusing the permanent collections in the galleries around the Museum, there seems to be a dearth of women artists.]

Thus,

coinciding with the Museum’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Plan, it seems it is necessary to point out that the exhibit’s work is by all women, though

more context on the why

in the exhibit didactics would be beneficial.

The exhibit statement reads:

“From printmaking’s beginnings more than 500 years ago, techniques such as lithography and etching were often considered too physically demanding for women to pursue professionally.”

However, this statement reads overly simplistic; in fact, women (though mostly rich and/or elite) were actually making prints since approximately the 16th century. Moreover, who and why was the process considered too demanding? Perhaps the professional male printmakers, in charge of the presses, deemed it as such– and this message transferred through the institutions and into art history, when in fact, really, it was a message of power.

However, this statement reads overly simplistic; in fact, women (though mostly rich and/or elite) were actually making prints since approximately the 16th century. Moreover, who and why was the process considered too demanding? Perhaps the professional male printmakers, in charge of the presses, deemed it as such– and this message transferred through the institutions and into art history, when in fact, really, it was a message of power.

Above: Princess Sophie of Saxe‐Coburg‐Saalfeld, “A Sheet of Sketches and Studies: Two Figures, Eight Heads, a Horse, Two Flowers” (1795), etching, New York Public Library Collections.

Control of presses controls the output and thus, whose stories are expressed and dispersed.

A little picking apart of that message could impact the viewer’s understanding of the why and how not only of women in print, but art history and its understandings, generally.

The CAM new acquisitions, are indeed impressive, from works by Kara Walker to Polly Apfelbaum and Chitra Ganesh to Mavis Pusey—presenting a broad diversity of genre, technique, era and perspective. Along with the brief contexts near each work, sub-sections would contextualize and honor the works even more.

Though, unfortunately,

the two small galleries hardly allowed each work to breathe and viewers to take them in with proper space.

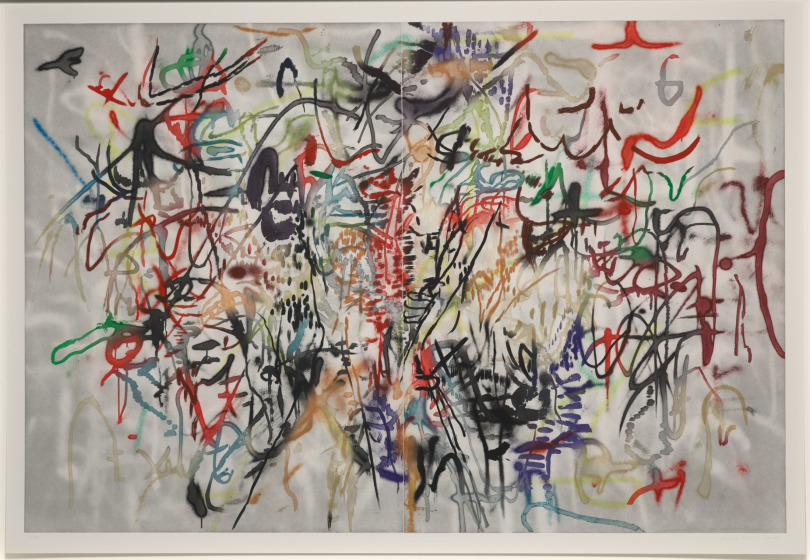

The largest print, the lovely,

expressive gestural aquatint by Julie Mehretu (American, b. 1970), Six Bardos: Hymn (Behind the

Sun) (2018) (right), welcomes visitors in the hallway at 127.6 x 186.1 cm. © Julie Mehretu

The rest of the works aren’t extremely small, but aren’t any larger. Not reflective of the careers of each artist which exemplify substantially strong presence, the small size of works and space yields a

yearning for a brighter,

bigger space to honor them in.

[Note: the Derrick Adams: LOOKS exhibit resides in a beautifully lit, high-ceiling gallery. His rich, outstanding, brightly colored paintings of wigs on mannequin heads are tremendously bigger than the largest print in Women in Print, and understandably displayed in this larger space. Still, the curating of Adams’ exhibit is noticeably more contextual, with commentary from community members about the content of the exhibit, and an exploration of the topic in general as well.]

I didn’t head into the Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure exhibit because it was a paid ticket exhibit (though I love the artist). The promotional text explains that the solo exhibition of the male artist includes 60 works and a fully illustrated exhibition catalog with multiple essays by recognized scholars. Since I did not view the exhibit, I cannot review it; however,

seeing a solo exhibition of one artist with over double the works in a paid ticket exhibition

next to

a group exhibition of 26 works of multiple artists with no noted accompanying publications,

on the surface,

exudes a traditional, patrilineal solo male genius perspective.

Paying attention to display and didactics is important as it is such a privileged perspective of the institution, one that often gets overlooked by gallery viewers though is extremely impactful.

Women and minority artists have not only been marginalized in collections,

but in textbooks

which translates into institutional understanding,

which finds its way to Museum labels and display,

and into the minds of viewers.

It is my hope that by writing such reviews more people can pay attention to the perspectives on display and didactics (whose story is told?) in exhibitions.

All of this said, the new acquisitions in this exhibition are amazing.

While I visited, there were student volunteers in the galleries waiting to discuss and further contextualize the works on view, a fabulous way to engage viewers deeper. My favorites include the aforementioned Mehretu, its luscious movement and rich colors provoke immediate attention across the page. The student volunteer kindly informed viewers about the artist’s complex, multi-layered process, and its relation to cave painting and calligraphy.

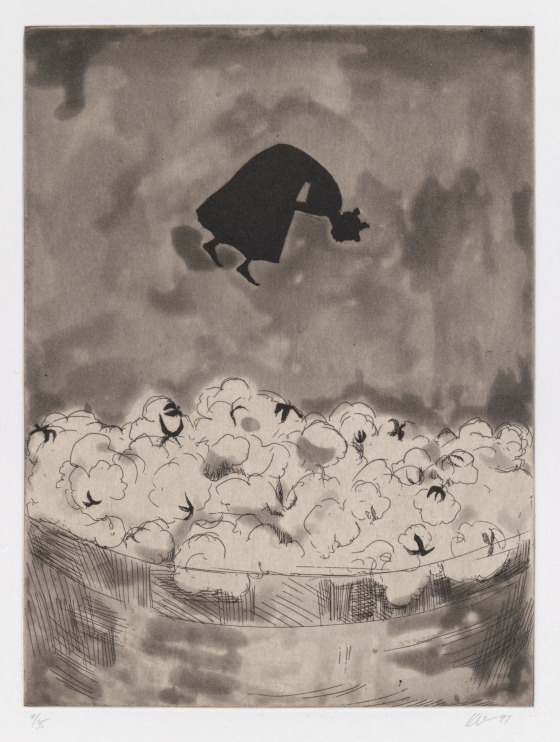

A modest grayscale etching by the esteemed contemporary artist Kara Walker (American, b. 1969) around the corner in one of the galleries, Cotton (1997) (left) depicts a silhouette of a woman in a dress above a bowl of cotton balls. The woman may be falling or spiraling; the image definitely evokes ill fate, similar to Walker’s notable larger installation works exploring issues of race, gender and power throughout American history.

A modest grayscale etching by the esteemed contemporary artist Kara Walker (American, b. 1969) around the corner in one of the galleries, Cotton (1997) (left) depicts a silhouette of a woman in a dress above a bowl of cotton balls. The woman may be falling or spiraling; the image definitely evokes ill fate, similar to Walker’s notable larger installation works exploring issues of race, gender and power throughout American history.

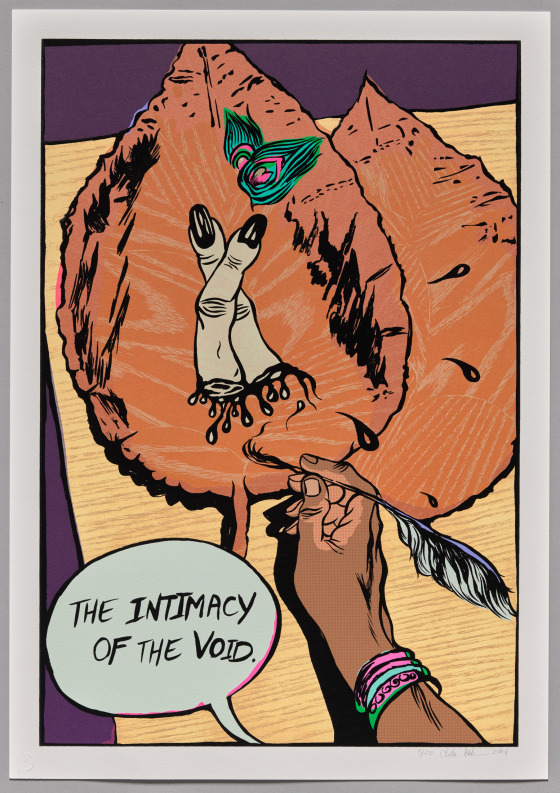

The series of four colorful, comic-styled prints by Chitra Ganesh (American, b. 1975) were especially provocative and exciting. Intimacy of the Void (2014) (below © Chitra Ganesh/Durham Press, 2014), a screenprint and woodblock print, shows a pink-braceleted hand drawing, with a feather onto big orange leaves, two dismembered fingers, and green pink-hearted feather, with a speech bubble pointing to what would be the artists’ head (in viewer’s gaze): “THE INTIMACY OF THE VOID.”  Ganesh draws upon her experience as a daughter of Indian immigrants in an oeuvre that includes work across media including: charcoal drawings, digital collages, films, web projects, photographs, and wall murals. This comic inspired series provokes questions of power, and sexuality through her use of body, space and viewer perspective.

Ganesh draws upon her experience as a daughter of Indian immigrants in an oeuvre that includes work across media including: charcoal drawings, digital collages, films, web projects, photographs, and wall murals. This comic inspired series provokes questions of power, and sexuality through her use of body, space and viewer perspective.

So many standouts in this exhibit; Ambreen Butt’s (Pakistani, 1969) Daughter of the East suite of five etchings (2008) based on photographs of women protesting at the Red Mosque in Islamabad, abstract and make beautiful such complex events. Amy Sherald’s (American, b. 1973) stunning Handsome (2020) color screenprint presents a strong young man in Sherald’s traditional gray skin tones,

standing confidently

with a strong gaze at the viewer,

eliciting innate respect,

as this collection.

The exhibition, with its display reconsiderations, definitely is worth a visit, exemplifying the strength and breadth of talent that is women in print.

Thanks for reading; stay tuned for my next review…if you appreciate the content and would like to support my work, please share with a friend and consider a tip!

What is this series about? Check out my introduction here.

~Sally